You May be in VC but not know it: OCIOs versus “The Magnificent Seven”

While OCIOs performed well in 2023 overall, within their public equity allocations few OCIOs successfully positioned themselves to take advantage of key equity market dynamics of 2023. This briefing examines the reasons why that was the case. In particular, we look at the impact that the “Magnificent Seven” performance phenomenon had on OCIO performance, and the stealth “megacap venture” allocations that have been growing in institutional portfolios.

The Year of “Negative Alpha” In Public Equities

Across the 50+ OCIOs that we monitor, we have seen many cases of strong alternatives performance, yet we have not found an OCIO that exhibited meaningfully positive alpha in their public equity allocations in 2023. Several OCIOs described the 2023 experience, where gains from the top seven market cap companies [the “Magnificent Seven”] exceeded the gains for the entirety of the rest of the S&P 500, as a “more than three standard deviation event.” They believe equity markets are primed to mean-revert, that is, returns on the rest of the stock market will catch up to the Magnificent Seven returns, or that Magnificent Seven valuations will fall back in line with market norms.

We approach this “mean reversion” line of thinking with a note of caution. It sounds similar to other mean-reversion themes over the last 10 years: for value stock performance to catch up to growth stock performance, or for European equities performance to catch up with U.S. equities performance. In both instances, there has yet to result in a meaningful catch-up of value or performance relative to U.S. growth and U.S. broad market index performance.

The Magnificent Seven

The impact of the performance of the Magnificent Seven on OCIOs’ 2023 equity performance should not be overlooked. You have probably seen this performance data for 2023 but it is worth revisiting:

Magnificent Seven Average: up 111%

S&P 500 Capitalization Weighted: up 24%

S&P 500 Equal Weighted: up 11%

MSCI ACWI: up 20%

The very large difference between the capitalization weighted and equal weighted gains reflects both the large Magnificent Seven returns, and the now-29% share of the S&P 500 that the Magnificent Seven represent. The 13% gap between the equal weighted and capitalization weighted returns means that your experience seeking alpha in public equity markets depended almost entirely on the extent of your allocation in the seven largest megacap stocks last year. If your OCIO’s strategy is to find talented public equity managers who pursue unusual sources of alpha in overlooked investment themes, your OCIO has probably significantly underweighted the Magnificent Seven megacap stocks. Thus, your public equity return might be somewhere closer to the 11% equal-weighted gain than the 24% market cap-weighted gain. If your OCIO mostly allocated public equities to indexes, or was careful to align your underlying stockholdings’ weights with the market capitalization weights, your public equity returns were probably closer to the 24% return.

Investors fall in and out of love with specific assets over time and you likely have heard of the nifty fifty, Tech Bubble, etc. over the years. The Magnificent Seven are viewed as a group much like the old FAANG stocks of only a few years ago. (Facebook (now Meta), Apple, Amazon, Netflix, Google (now Alphabet).) The change from FAANG to the Magnificent Seven is the addition of Microsoft, Nvidia and Tesla, and dropping of Netflix. The incessant AI chatter and hopes are tempting investors that the megacap outperformance will continue.

So are the Magnificent Seven a fad that will mean-revert, or is something else going on?

An Alternative View: Are the Magnificent Seven the Premiere Venture Investors?

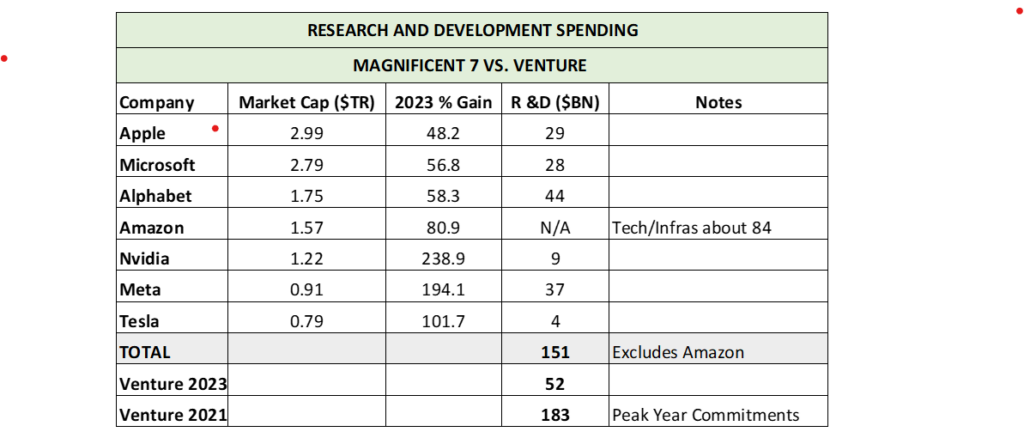

While we are familiar with macroeconomic debates about monetary policy, a key interest of macroeconomists has been identifying the reasons for economic growth. Technological advancement is viewed as a major driver in macroeconomic models, and the United States’ private sector has been a major contributor to economic growth by investing heavily in research and development (R&D). As investors, we think of venture capital as a major area of technological evolution, but since we are more aligned with allocators, not stock analysts, we can easily overlook the extent of technology investing derived from publicly-held companies. Let the data do the talking:

Sources: market cap and 2023 % Gain are from multiple market data sources; R&D figures are from annualization of third quarter R&D spending from third quarter financial disclosures of each company, total commitments to venture capital funds by year provided by Pitchbook.

Notes: Amazon does not break out research and development (R&D) expenses from spending on all technology and infrastructure.

Clearly we are equating venture investing with R&D investing, yet we accept this linkage as being very close, since almost all R&D spending by these companies will be invested either in developing new technologies or finding new applications for existing technologies. That’s pretty much what almost all venture capital managers seek to do.

From the data, we can see that the Magnificent Seven’s R&D budgets far outstrip the R&D budgets of the venture capital industry in 2023. Recognizing that 2023 was a weak year for venture fundraising, we thought it important to compare as well to venture’s peak fundraising year of 2021. Even then, the entirety of the venture capital industry likely just barely kept up with the R&D spending of the Magnificent Seven.

Are Magnificent Seven Investors Unknowingly the Biggest Venture Investors?

So the Magnificent Seven are big R&D spenders, but how much of an investment in these companies is really a venture-like investment? Each firm already has a well-defined source of cash generation from their ongoing businesses, after all. A quick look at their financials shows that R&D spending represents about 10 to 25% of these companies’ revenues, and 25% to 100% of their profits, in the third quarter of 2023. Those are big commitments!

We would argue that the outstanding returns of the Magnificent Seven represent the result of many years, even decades, of venture program-like investing. Most recently, cloud computing and storage have brought major new business lines to Microsoft and Amazon, with others trying to catch up. In fact, cloud computing, a business that barely existing 10 years ago, represents the majority Amazon’s revenues now. AI opens the potential for vast new markets and could stimulate more technological advancements in sciences, law, education, medicine, and other areas, though it is possible that the value from AI accrues almost entirely to clients rather than the producers.

The net result is that investing in the Magnificent Seven may be like investing in a blend of mature businesses alongside well-established and successful venture investing programs. While determining the mix between the two may be beyond the scope of this discussion, such considerations haven’t stopped us from positing a rule of thumb: if company management is spending 25% to 50% of profits on R&D, then what is the venture mix of an investment in that firm? Is it close to that profit share (we’ll just refer to this as “megacap venture”). Moreover, since the Magnificent Seven represent about 29% of the S&P 500, does that mean that institutional investors’ indexed U.S. public equity allocations are implicitly 7 to 15% invested in venture? After adjusting for non-U.S. holdings in equities, that would be an “average” global equity investor is 5 to 10% invested in “megacap venture.”

You may already be a substantial venture investor through your indirect “megacap venture” allocation, even if you do not have a formal venture allocation.

Venture Investing and Volatility

Experienced alternatives allocators have many stories to share about volatility in their investment strategies, and no major group of alternatives investments is riskier than venture investing. Some of that riskiness clearly shows up in the volatility of the megacap stocks. However, the operational aspects of R&D investing in a corporate framework are quite different from within a venture-backed startup’s framework. Incentives to venture founders are exceptionally strong. Conversely, oversight by talented project managers in a proper corporate setting may allow for a more efficient allocation of resources among R&D efforts, both to deploy capital and to cease investments in less promising ventures.

Reconciling the Megacap Venture Experience with our OCIO’s Allocations

Here we face the crux of the problem. If an alpha-seeking allocator will look for equity managers with an “edge” for investing in or trading stocks that will inevitably scan the universe broadly for best ideas, the result for 2023 will be greatly reduced allocations to the top-performers, the Magnificent Seven. That allocator will likely see a substantially negative alpha in their liquid equities allocations, despite the talents of their underlying equity managers.

However, looking at a partial picture can be misleading. Many OCIOs are keenly aware that private equity, growth equity, and venture capital investment programs are inherently turbocharged growth equity allocations over the long term, so they tend to hold value biases in their liquid equity portfolios to create a more balanced growth/value portfolio. In other words, if your OCIO has been investing in venture and growth equity strategies, it is likely that you will have positive experiences in your private holdings offsetting the lagging performance in the public equity portfolio over the long term.

Conclusion #1: Don’t Expect Mean Reversion, Megacap Venture-Like Investments Have Succeeded

We see a permanent change in the U.S. public equities market structure. Technological innovation appears to favor very large companies, rather than large numbers of small companies. Now we are projecting outside our core expertise by pretending we are stock analysts, but we’ll share our perspective on the seven companies. Unlike in prior “tech bubbles,” the tech giants [MSFT, AAPL, GOOG, AMZN, FB] possess true “know how” that is difficult to replicate, defended by myriad patents, and fortified by continuing research. We see an oligopolistic market structure, with wide profit margins and stable to expanding market share, as a long-term structural change in the public equity market that will continue to flummox the talented alpha seekers. We also see these vast businesses as exceptionally difficult ones for equity managers to understand at a level where they have a material “edge” over the market. The net result is that about 25% of the public equity market represented by these five stocks is both critical to asset allocators and opaque to alpha-seekers.

We also believe that TSLA and NVDA, both excellent firms, face greater risks in their more-concentrated business models; TSLA because they face rising competition from auto manufacturers entering the EV market and waning EV market growth, and NVDA simply because their already-high valuation implicitly depends on programmers failing to increase the efficiency of large language models and other AI programs by 90%+ [which is believed possible], and the failure of meaningful competition to arise over the next few years. The great stock pickers can hopefully discern better than we can how material these risks are to TSLA and NVDA.

The net result: generating alpha from large and megacap public equity allocations is harder than ever, and under allocating to megacaps likely means under allocating to some of the U.S. economy’s greatest economic growth engines.

Conclusion #2: What We Would Like Every OCIO to Consider

As search and evaluation consultants, we are pleased that the impressive array of OCIO managers we recommend continues to produce returns for their clients meaningfully above OCIO market benchmarks. These OCIOs have created a culture of excellence that extends throughout their investment process, and they often achieve their greatest alpha-generating successes with their alternative investment programs.

While OCIOs also strive to generate alpha with their selection of public equity managers, now may finally be a time of reckoning. Finding alpha investing in large cap equities is exceedingly difficult, and we rarely see active managers [or hedge funds, for that matter] who have truly demonstrated an edge in analyzing megacap stocks. Conversely, equity managers that focus on stocks that they can analyze with some edge will likely be underallocating your capital to megacap stocks, leaving you underweighted to that critical growth engine, “megacap venture.”

We ask our talented OCIO managers to consider [again] the possibility that increased use of indexing in the large and megacap parts of the public equity markets may actually be desirable, unless the OCIO has rare capacity with the very short list of alpha-generators in large cap markets. OCIOs need not prove they produce alpha everywhere, and it is better to concentrate efforts where they have demonstrated a meaningful advantage.

We would be pleased to discuss this topic further, and to hear any feedback or experiences you may wish to share with us. We can be reached at 917-287-9551 or at info@manageranalysis.com.

Manager Analysis Services LLC

February 1, 2024